PETRA, JORDAN (AFP) – Herds of hardworking donkeys once carried herds of tourists on the rocky trails of Jordan’s Petra, but visitor numbers plummeted amid the pandemic and the loyal animals are unemployed.

“Before the coronavirus, we all had work,” said Abdulrahman Ali, a 15-year-old donkey owner in the old, rock-cut desert town, where the sure-footed animals carry tourists up steep paths in the blazing sun.

“The Bedouins of Petra made a living and fed their animals,” he said, waiting for food from a charity, explaining that many owners today have difficulty paying for the feeding.

In 2019, the number of visitors to the UNESCO World Heritage exceeded the million mark for the first time.

But in March 2020 the famous tourist destination was closed and the crucial income for tourists dried up.

TOP & BOTTOM: Tourists ride donkeys and horses while visiting the ancient city of Petra, Jordan; and Jordanian locals meet up with a donkey in the ancient city of Petra in Jordan. PHOTOS: AFP

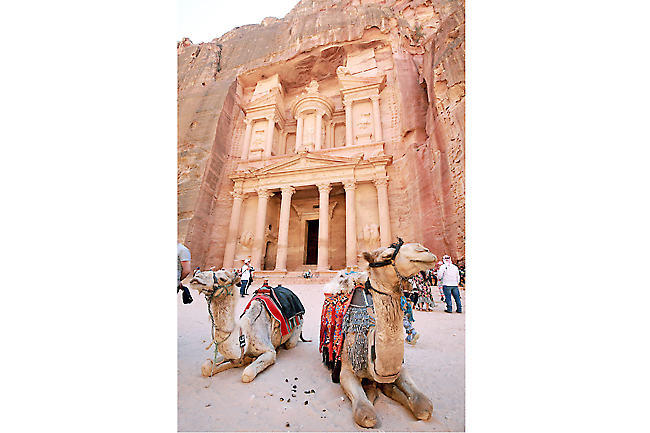

Camels waited outside the treasury in Jordan’s ancient city of Petra

Camels waited outside the treasury in Jordan’s ancient city of Petra  TOP & BOTTOM: Jordanian donkey owner Abdulrahman Ali, 15, feeds his animals at the PETA clinic and treats animals used by locals to transport visitors to the Jordanian ancient city of Petra; and A Jordanian donkey owner waits for customers in Jordan’s ancient city of Petra costume

TOP & BOTTOM: Jordanian donkey owner Abdulrahman Ali, 15, feeds his animals at the PETA clinic and treats animals used by locals to transport visitors to the Jordanian ancient city of Petra; and A Jordanian donkey owner waits for customers in Jordan’s ancient city of Petra costume

DEPENDING ON TOURISM

“When tourism stopped, nobody could buy food or medicine,” said Ali, who could earn up to $ 280 on a good day and support his mother and two brothers.

“If you have a little money, you can now spend it on your own food, not on your animal.”

Before the pandemic, tourism accounted for more than a tenth of Jordan’s GDP, but revenue plummeted from $ 5.8 billion in 2019 to $ 1 billion last year, according to government figures. Tourist numbers have been slowly recovering since Petra reopened in May.

Only about 200 visitors a day come to Petra, compared to more than 3,000 before the pandemic broke out, said Suleiman Farajat, head of Petra’s regional development and tourism agency.

Farajat said about 200 guides used up to 800 animals – including horses, camels and mules, and donkeys – for tourist rides across the desert.

The economic wave of tourism was widespread.

“Before the crisis, 80 percent of the region’s residents were directly or indirectly dependent on tourism,” said Farajat.

“Not only livestock owners were affected by the pandemic, but also hotels, restaurants, those with souvenir shops or shops and hundreds of employees have lost their jobs.” Many donkey owners turn to a clinic supported by the animal rights organization PETA, where veterinarians treat abused and malnourished donkeys free of charge.

“Before the coronavirus, my family and I owned seven donkeys that were working in Petra,” said Mohammad al-Badoul, 23, as he waited with four other donkey owners to fill a sack with animal feed.

“We had to sell them for lack of money. Now we only have one and I can hardly feed it. “

HUNGRY

Egyptian veterinarian Hassan Shatta, an equine surgery specialist who runs the PETA clinic, said he started a donkey feeding program late last year.

“During the Covid-19 lockdown and the lack of tourism, people could no longer afford to feed their animals,” Shatta said.

“Some of them starved to death and we picked them up and brought them here,” he added, noting that around 250 animals were treated, with around 10-15 cases a day.

In the past, PETA had treated animals with deep cuts caused by beating or abuse, but Farajat, of Petras Tourism Board, said the donkeys’ working conditions were “not so bad” now.

But there are plans to replace some of the traditional donkeys with a new system of 20 electric cars that will be introduced by the tourist board next month. The cars are “driven by the animal owners,” Farajat said.

Farajat hopes that the switch to electric cars will put an end to criticism of the mistreatment of animals.